In this presentation, Gary Klein shares important information about air source heat pump water heaters (HPWH), with particular attention paid to where the warm air comes ...

Mixing Passive and Active Heaters Can Lead to Problems

Sometimes, you just have to think like air.

The house had been sitting on this old Connecticut street for more than 100 years. Children, grown and long gone, had once skipped across its wide lawn and watched in wonder as the new cars clattered by. Grownups sat in the shade of the latticed porch and waved off the summer heat with paper fans. If you close your eyes, you can still see them there.

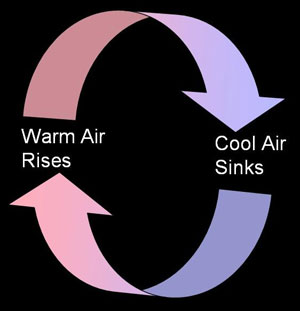

In the winter, they sat inside the house by the ornate, cast-iron radiators that ringed the room with warmth. Down in the basement, a behemoth of a coal-fired boiler heated water. The warmed water became buoyant and rose upward toward the radiators. It displaced the denser cold water in the radiators, and sent it tumbling downward through the large pipes to the boiler where it too would be heated.

Systems such as these depend on natural convection. Hot water rises; cold water falls. It’s a simple principle, but to make the system work well and heat evenly without circulators or controls the Dead Men had to be very specific in the way they laid out a job. They had to size and angle the pipes just so. If they made a mistake, the convective currents wouldn’t happen and the house would be cold.

For more than 100 winters, the gravity-hot-water heating system in this old house had warmed the families who lived there because the Dead Men had done a superb job. But now, the new owner of the house was changing things. He was leaving the old radiators with their raised metalwork; they were far too beautiful to remove. Most of the old piping would also stay.

There would be a new boiler, of course. There would also be a circulator and zone valves, and controls. The new boiler would have a bypass line to protect it from condensed flue gasses. There would also be an air separator.

The new boiler would also have an additional zone because the owners had decided to extend the old house so they could have a larger kitchen. Their architect had done a good job of matching the addition to the original house. The heating engineer now had to figure out the best way to warm this new space.

After much consideration, the engineer decided to use two, recessed floor-convectors in front of the wide kitchen windows. He would also use a kick-space heater beneath the sink cabinet on the other side of the kitchen. He calculated the heat loss of the new kitchen very carefully and sized the convectors and the kick-space heater very accurately.

The architect liked the engineer’s choice in heaters because the recessed floor-convectors had attractive brass grates that fit well with the home’s Victorian character. The kick-space heater, well, it would be practically invisible under the cabinet.

The contractor installed the new boiler, made the changes to the system and piped the new zone. The general contractor finished work on the home and everyone waited for winter to arrive.

And arrive it did. That first winter was much colder than normal and the weather put the new kitchen zone to the test almost immediately.

It didn’t work.

The homeowners called the heating contractor to complain. The temperature hovered around 62 degrees, even though they had the thermostat set for 72 degrees. The contractor went to the job and checked things out. Everything seemed to be working properly, except that the kitchen was too cold. He called the engineer.

The engineer showed up on the job and went over the mechanical aspects of the system. He could find no fault. He checked his heat-loss calculations, and they seemed fine. He turned to the contractor and said, "Well, what are you going to do?" This bewildered the contractor because he thought the engineer was in charge.

"What do you mean what am I going to do?" the contractor asked.

"What do you mean what do I mean?" the engineer said. "You obviously did something wrong. My calculations are correct. The heaters are sized properly. There must be something wrong with your installation."

"But you designed the installation!" the contractor protested.

"I know I did," the engineer shot back. "And it’s a good design. You must have made a mistake in the installation."

"Where? Do you see anything here that deviates from your plans and specs?" the contractor asked in frustration.

"There must be something stuck in the pipes," the engineer said. "Did you flush the system? Have you checked the flow rate? The system is operating as though it’s not getting enough flow. You should check your work. My design is correct." And with that, the engineer left.

The homeowner wanted to know why it was still cold in his new kitchen, and with the engineer gone, the contractor was left holding the bag. He decided the engineer might be right about something being stuck in the pipes. These things happen. So he flushed the system and installed flow meters. The flow meters showed the flow to be what it was supposed to be. The contractor called the engineer and after some more frustrating conversation they both began thinking about the movement of air rather than the movement of water. The pipes could deliver hot water to the recessed convectors and the kick-space heater, but unless the air could remove the BTUs from those hot surfaces, the kitchen would remain cold. They finally got together and used their imaginations to see how the air would move in a room served by heaters such as these.

This is what they reasoned:

The recessed floor-convectors work by convection. These units heat the air above their elements and cause it to rise. The cooler air along the floor will then fall into the convector’s recessed trough and be heated. It, in turn, will rise and create a convective movement of air within the room. The movement of air will be very similar to the movement of water in the ancient gravity hot-water system that had served the old house for so many years. The principle was the same.

Now the kick-space heater also worked on convection, but it had a fan. It used that fan to draw in the air near the floor. It heated the air, and then it kicked it back into the room - right at floor level. The heated air rose toward the ceiling and tumbled the rest of the air in the room in a second convective current.

And it was then that the contractor and the engineer began to consider what happens to the recessed floor-convectors when the kick-space heater is shooting hot air across the floor? How can warm air rise out of the recessed convector if there’s no cooler air to replace it?

It occurred to the contractor and the engineer that these two types of heaters will never get along within the same zone. Each unit is looking for something different and the problem will always crop up on the coldest days of the year because that’s when both units are needed. Until they began to use their imaginations, the engineer and the contractor couldn’t see those air currents fighting each other. Once they opened their eyes, though, the solution was easy.

They drilled some holes in the bottom of the recessed convector. That allowed air to circulate up from the basement and the problem was solved.

Leave a comment

Related Posts

In this all-technical three-hour seminar, Dan Holohan will give you a Liberal Arts education in those Classic Hydronics systems. He’ll have you seeing inside the pipes as...

We always have turkey for Thanksgiving. I mean who doesn’t? My job wasn’t to cook it, though; it was to eat it.